The draft of the new Tunisian constitution permits the application of Islamic law through the back door. It puts the separation of state and religion into question, once a major achievement of modern Tunisia.

On 30 June 2022, the long-awaited draft of the new constitution was published.

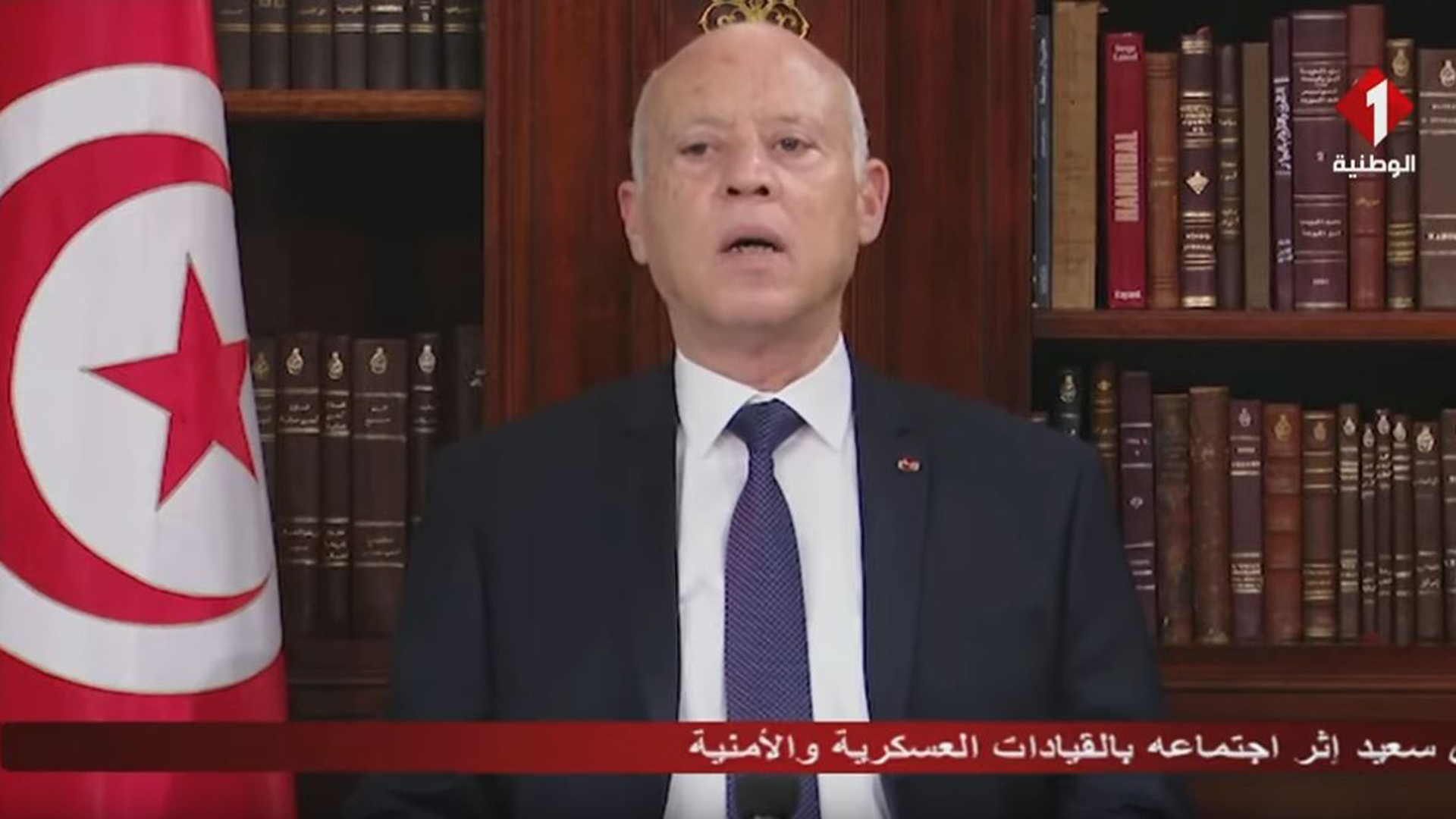

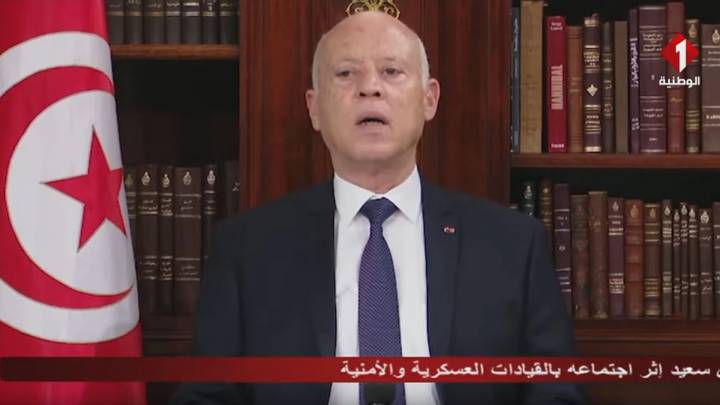

The draft, which consists of 142 Articles structured in 11 chapters, will be put to referendum on 25 July 2022, as per the President’s roadmap of 13 December 2021. According to the Roadmap, the body tasked with drafting the Constitution is the National Consultative Committee (NCC) chaired by Sadok Belaïd, constitutional law professor and former dean of Tunis' Faculty of Legal and Political Sciences. However, just within hours after its publication, the jurist has disowned the draft claiming that the President has unilaterally introduced major changes and issued radical alterations to the proposed constitution.

We have been denied a transparent explanation of the drafting modality and the source of the new Constitution

This confusing move has raised significant skepticism about the President’s intentions and demonstrates the lack of transparency in the procedure of drafting the Constitution. Considering the unclarity around the drafting process and the noticeable differences between the two versions of the Constitution, I believe, as a Tunisian citizen, that we have been denied a transparent explanation of the drafting modality and the source of the new Constitution. From my position as a lawyer, I also estimate that such information has a “public interest” nature thus shall be subject to a reasonable public examination and legitimate legal and political inspection. The opacity around such information is a presumption of the establishment of the “one-man rule”, which is a threat for the Tunisian fragile democracy.

Apart from the obvious deviation from the roadmap – that was once agreed upon – it is particularly Article 5 of the draft that has triggered the biggest controversy, I think. The language of Article 5 paves the way for including a clear reference to Sharia into the constitution. It is worth mentioning that the former Tunisian constitutions have always maintained a secular character in both 1959 and 2014 versions despite the explicit reference to Islam. The latter has only served as the official “religion of state”.

While the chairman of the NCC has confirmed on several occasions before the publishing date that there would be no reference to Islam in the draft of the constitution, Article 5 of the released version stipulates that "Tunisia is part of the Islamic Umma. Only the State shall ensure that the precepts of Islam are respected in terms of human life, dignity, property, religion, and freedom.” This article, if passed, will replace Article 1 of the constitution of 2014, which provides that “Tunisia is a free, independent, sovereign state; its religion is Islam, its language Arabic, and its system is republican. This article may not be amended.”

It can generate ambiguous readings and potential contradictory interpretations

This “superfluous” reference to the “belonging” to the Muslim nation and the exclusive role of the “preserver of the goals Islam” attributed to the State can only lead to vagueness thus generate ambiguous readings and potential contradictory interpretations of the text.

First, the concept of the “Islamic Umma” is not only difficult to define but also hard to convey in a legal setting. Many scholars would read this Article 5 as rather granting the State the possibility to be the only actor in the religious sphere, than providing for the instrumentalization of religion in the political field.

Second, the origin of the expression and its idiomatic meaning can largely explain the skepticism behind its use. The expression has been coined to mean a theological concept stressing the importance of the organization of society along Islamic precepts namely Sharia. In my view, referring to the purposes of Sharia in the constitution may seriously challenge the sacredness of the rule of law and its exclusive task of regulating rights, freedoms, citizenship, and equality. Concepts like polygamy, inequality in inheritance and punishments according to the Islamic rules, which are alien to the Tunisian society, may be introduced within the Tunisian legal framework if the abovementioned Article 5 is interpretated in a way to consider the preservation of “The precepts of Islam” as a summons to apply Sharia as the main source of law in Tunisia.

The risk is that such reference could permit state leaders, lawmakers, and the courts to refer to “precepts of Islam” as a basis for undermining human rights, especially when reviewing laws related to gender equality or individual rights and freedoms, on the grounds that they are alleged to contradict religious principles.

Tunisia has always been an example of the secular state

The key question that came to mind while reading this Article 5 is whether Tunisia of today needs an affirmation for its “affiliation” to the Islamic Umma. In fact, Tunisia, even with a vast majority of its population being Muslims, does not endorse Sharia law, but rather relies strongly on European influenced codes. Tunisia has always been an example of the secular State that clearly adopts the separation between the civil State and religion.

I consider that Tunisia with its exceptionality in providing for protection of the family status and women’s rights and freedom of consciousness is neither at the stage of seeking validation regarding its adherence to Islam nor does it necessitate a text in the constitution to address the protection of fundamental rights. Citizens who are conservative in their religious views are undeniably part of the Tunisian diverse society and shall be protected by the law and the democratic values adopted by the state. The latter is the most efficient guarantee for the protection of citizens’ rights notwithstanding their backgrounds and affiliations.

I will vote no because I believe that Tunisia, as one of the most progressive countries in the Arab-Muslim world that has successfully maintained a synthesis between the Muslim heritage and the imperatives of modernity, doesn’t need a constitution that may jeopardize its position as a pioneer of modernism, tolerance, and progressivism in the Arab world.

Meriem Rezgui is a Tunisian lawyer based in Berlin. She studied law and political science at the universities of Tunis and Berlin (Humboldt University). Among her professors in Tunis was today’s president of Tunisia, Kais Said.